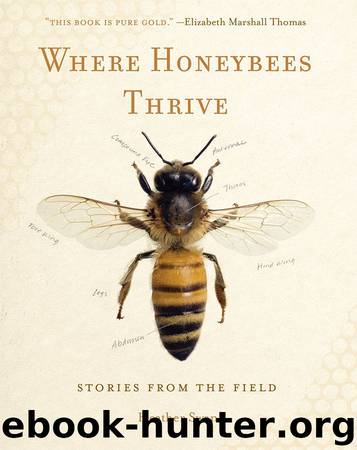

Where Honeybees Thrive: Stories from the Field (Animalibus: Of Animals and Cultures) by Heather Swan

Author:Heather Swan [Swan, Heather]

Language: eng

Format: azw3

Publisher: Penn State University Press

Published: 2017-10-12T04:00:00+00:00

Despite the conclusion of beekeepers across the globe, based on their field research, that neonicotinoid insecticides were likely contributing to increased bee mortality, some chemical company representatives, scientists and government regulators dismissed or disparaged their findings. Our view is that commercial beekeepers have real-time observational knowledge of the crisis facing honey bee pollinators and that we should take their research seriously. . . . Our point is not to say that commercial beekeepers always know best. Rather, it is to argue for more genuinely participatory research that brings beekeepers’ knowledge and scientists’ knowledge into a creative and egalitarian dialogue toward a fuller understanding of why honey bees are dying.

In September 2013, Suryanarayanan and Kleinman launched a “transdisciplinary inquiry” funded by the U.S. National Science Foundation involving the range of stakeholders on the ground—entomologists, ecologists, beekeepers, growers, government representatives, and humanitarians. In collaboration, they have designed experiments to save bees without tormenting them. In one approach, they’ve studied beehives in a variety of landscapes with varying amounts of pesticides, and then sampled pollen to see which communities are most effective, and why.

How might a beekeeper, who knows when bees visit particular flowers, help refine a study’s design? How can the knowledge of an ecologist help interpret those findings? How could a grower, who knows the timing and methods of chemical applications, help analyze these results? These conversations will eventually—it is hoped—affect policy and future research.

The summer of 2014 was the first season of Sainath’s alternative approach to bees, and he started by observing them in the landscapes in which they lived. As a research assistant to Sainath and his diverse team, I visited bees living at the edges of meadows full of wildflowers and hives nestled on the edges of corn and vegetable fields. We spent time talking to farmers and beekeepers about their habits, approaches, and concerns.

The life of honeybees cannot be divorced from the humans who work with them, count on them, love them. We opened hives and took note of their activities and their health. As we lifted the frames, Sainath whispered soothing words to the bees. As with his previous work, the new approach provokes complex emotions, but his nightmares are gone.

In an article that explores the “emotional ecology of field science” that occurs in multispecies relationships among scientists, horseshoe crabs, and red knots (a northern shorebird), science and technology scholar Kristoffer Whitney writes, “Empathy, wonder, and technological and methodological enthusiasms make science in the Delaware Bay happen, and this is visible in the prosaic experiences of wildlife researchers and managers there. These scientists move, however, from research sites on the bay into multiple public, decision-making bodies, and these movements require the translation and obfuscation of the values underpinning their work bayside into forms socially acceptable in the context of rational bureaucracy.” Basically, Whitney suggests, we are not allowed to reveal the emotional valences that inform policymaking or the science it is based on. But science is informed already by emotion, by compassion, as it must be.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Art of Boudoir Photography: How to Create Stunning Photographs of Women by Christa Meola(18604)

Red Sparrow by Jason Matthews(5451)

Harry Potter 02 & The Chamber Of Secrets (Illustrated) by J.K. Rowling(3657)

In a Sunburned Country by Bill Bryson(3524)

Drawing Cutting Edge Anatomy by Christopher Hart(3509)

Figure Drawing for Artists by Steve Huston(3430)

Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban (Book 3) by J. K. Rowling(3339)

The Daily Stoic by Holiday Ryan & Hanselman Stephen(3287)

Japanese Design by Patricia J. Graham(3153)

The Roots of Romanticism (Second Edition) by Berlin Isaiah Hardy Henry Gray John(2901)

Make Comics Like the Pros by Greg Pak(2899)

Stacked Decks by The Rotenberg Collection(2867)

Draw-A-Saurus by James Silvani(2703)

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows (7) by J.K. Rowling(2701)

Tattoo Art by Doralba Picerno(2645)

On Photography by Susan Sontag(2621)

Churchill by Paul Johnson(2567)

The Daily Stoic by Ryan Holiday & Stephen Hanselman(2562)

Drawing and Painting Birds by Tim Wootton(2491)